LESSON 2.3

Audiences: Pedagogy

In 1964, the Dartmouth Conference was touted as a meeting of composition theorists who would try to address the problem of essays with generalized, boring subjects, a problem that had plagued student writing for decades.

The attendees voted almost unanimously that students should write about themselves, a decision heavily influenced by a call for relevancy in English classes as a result of the escalating Vietnam War. This new emphasis began being referred to as Expressivism and Expressionism (not to be confused with the art style of the same name), but more commonly was called personal-experience writing.

Interpersonal vs. Intrapersonal Writing

This shifted the emphasis from writing interpersonally –for others – to writing intrapersonally –writing for ourselves. This shift was so radical that Peter Elbow, whose book, Writing Without Teachers, became a bestseller, refused to publish any of his students’ work, saying that doing that would constitute a violation of their self.

Such writing is valuable, especially for children with mental illnesses or problems with fears of opening up to others, a problem that

Few people pointed out that in many cases Expressivism compounded.

Other Problems

1. De-emphasizing interpersonal writing and valorizing intrapersonal writing meant that students spent less – or little – time learning the structures and content of writing meant in college or the workplace.

A case in point: The students in RAHI (the Rural Alaska Honors Institute) were asked to write short essays for a placement exam. They were given two prompts:

• Write a brief essay about an important event in your life. How has it affected you since then?

• Write a brief essay about an important, specific economic change in your community. How has it affected the community overall?

There were 50 students in RAHI that year. Most represented the crème de la crème of their respective schools. Alaska schools had been inundated with Espressivism for several years.

On the first question, 80 percent wrote essays worthy of at least a B-.

On the second essay, only four students wrote essays worthy of at least a B-. Those four were among the six students from British Columbia.

2. When we write, we must be organized so our readers can understand us easily.

Audience

CHANGE. The following are audiences we usually should not write for:

- Our teacher

- Our parents

- Our classmates

- Our friends

We can communicate with such people by talking to them in person, by telephoning them, or by texting them.

Adults

Unless you are told otherwise, always assume you are writing for adults. That way, you will be ready to write for adults once you’re older (assuming you’re not an adult already 😊).

Adult Strangers

The adults should be strangers to you. If they are people you know, then assume they are strangers. That way, you will be more complete in what you have to say.

What All Adults Have in Common

Almost all adults have one thing in common: They are busy.

Almost all adults have one thing in common: They are busy.

Since they are busy, they do not want to read about what they already know a lot about. It’s a waste of their valuable time.

An Example

Let’s say you were asked, If you could be any wild animal, what would you be? Perhaps you answered like this:

If I were any wild animal, I would be a(n) ….

If I were any wild animal, I would be a(n) ….

Cheetah

Eagle

Giraffe

Grizzly bear

Lion

Monkey

Panda bear

Polar bear

Rabbit

Shark

Zebra

Which one is best to write about?

The answer? None of them.

You are writing for an adult stranger. You can assume that nearly all adults already know quite a lot about most animals named above. Sure, you might tell the reader something new, but for most people, reading about those animals would be a waste of time. And time is precious.

A Good Subject

Always select a subject that you feel the audience—

- Knows little about

AND

- Will find interesting

Another Example

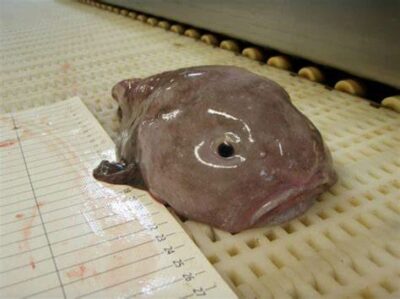

Here are some subjects that readers are likely to know little about and that are likely to be interesting:

But What Is Interesting?

How do you know what the audience (a) will know little about and (b) will find interesting?

You don’t know. Not for certain, anyway.

The answer, though, goes way back to the Ancient Greeks. They said it’s all based on common sense. For example, which is the audience less likely to know much about?

- A lion

- An ice worm

It’s an obvious answer. But are ice worms interesting?

They live inside glaciers. In the ice. And scientists don’t know exactly how they do it.

Will all potential readers find that to be interesting? No. But common sense tells us that most readers probably will. And so it’s a good subject.

Small Group Activity

Make a list of pets you feel readers would not know much about.

Writing About What We Find Interesting

Students often mistake subjects that they find interesting for what audiences find interesting. For example, perhaps you listed, “my dog, Spot” as a pet that readers would not know much about. However, unless Spot has done something extraordinary, they are unlikely to care about him, since he is only one pet among the billions worldwide.

Small Group Activity

Delete any types of pets from your list that readers are already likely to know about.

Individual or Small Group Activity

Complete the exercises: Barbados

St. Lucia